Within two hours of landing in Shanghai after flying for over 20 hours from Boston this summer, I was weaving through traffic on a yellow rental bike, following my son along Shanghai’s narrow streets. Moments before, when he had selected the bike from a clump of them on the sidewalk, scanned the bike’s ID with his phone, unlocked it, and handed it to me, I had said, “I’m not sure I can do this.”

Within two hours of landing in Shanghai after flying for over 20 hours from Boston this summer, I was weaving through traffic on a yellow rental bike, following my son along Shanghai’s narrow streets. Moments before, when he had selected the bike from a clump of them on the sidewalk, scanned the bike’s ID with his phone, unlocked it, and handed it to me, I had said, “I’m not sure I can do this.”

“But you mountain bike,” he said.

“It’s not the biking I’m worried about. I’m not putting it all together too well.” I waved vaguely into the air and got on the bike anyway. Off we went. Oddly enough, despite the narrow streets and jet lag, we pedaled among Audis, BMWs, Mercedes, Toyota Camrys, and the occasional Porsche and Jaguar, as well as bright white-and-green buses, and zillions of scooters and bikes, going from the language school where he was studying Mandarin for the summer to his apartment without anyone dying.

“It’s because the drivers don’t want to kill bicyclists in Shanghai the way they do in the U.S.,” he said. The key to survival, as a pedestrian or bicyclist, is to pick your line and stick to it. People will drive around you.

And that more or less characterized my one-week trip—one unexpected experience after another. I had thought of China as an ancient kingdom and now a developing country but not nearly as modern and sophisticated as the United States. Wrong. At least when it comes to Shanghai.

For starters, so much of Shanghai is brand new, built in the last twenty years or so, including a shiny, fast subway with about 20 different lines, in contrast to Boston’s delay-plagued, rattling trains. China has the world’s only magnetic levitation train, which reached 430 kilometers per hour as I rode in from the airport, and soaring skyscrapers, towering  hotels, and massive apartment blocks. Luxury stores abound—Armani, Gucci, Cartier, YSL, Prada, and Zara—and small boutiques for discriminating shoppers since Chinese consumers account for one-third of the global luxury market.

hotels, and massive apartment blocks. Luxury stores abound—Armani, Gucci, Cartier, YSL, Prada, and Zara—and small boutiques for discriminating shoppers since Chinese consumers account for one-third of the global luxury market.

From riding the subway, I was certain no one in the city was over 30 or anything other than gorgeous. Women dressed in short-shorts or pretty skirts and tops, crammed into train cars, glued to their iPhones. I wondered what Deng Xiaoping would say about their scant clothing or the prevalence of apps. Or would he just be glad the Communist Party was still in power and, overall, the level of economic prosperity had risen for most people, although much more for some than for others?

Another discovery was how international Shanghai is. Take the restaurants. From all-you-can-eat-and-drink taco places to high-end coffee shops roasting their own beans, you name it, you can find it. During my week there, I had the best soup dumplings, a Shanghainese speciality, as well as the best hash browns at a diner, not to mention a perfectly grilled rack of lamb at a farm-to-table place. But then again, Shanghai has been an international center since the Opium Wars, when Great Britain forced opium on the Chinese people around1840 to help balance its trade deficit with China caused by the British love for tea.

Amidst the gleaming luxury cars on the narrow streets were not only peo ple on bikes and scooters but men pedaling bicycle rickshaws, hauling stacks of flattened cardboard boxes or pieces of scrap wood piled high. One bicycle rickshaw was loaded 10 feet high with huge bags filled with empty plastic bottles. The recycling man, I guess.

ple on bikes and scooters but men pedaling bicycle rickshaws, hauling stacks of flattened cardboard boxes or pieces of scrap wood piled high. One bicycle rickshaw was loaded 10 feet high with huge bags filled with empty plastic bottles. The recycling man, I guess.

Also unexpectedly, the air quality was not wretched. Part of the reason lay in the scooters zooming up behind me on the sidewalk before I could even hear them. It was my son who clued me in. Nearly all of the scooters and cars are electric. Not a single bus or truck belched noxious diesel smoke. Central planning has some upsides, compared to our buffoon-in-chief rolling back auto efficiency standards so we can burn the maximum amount of fossil fuels. If Xi Jinping, or his top advisors decide on something in China, it happens.

That is not to say that people enjoy the freedom we have in the United States. I was watching CNN one evening in my hotel room while brushing my teeth and the screen went dark for over five minutes after the announcer mentioned the problem of people-to-people lending in Beijing. Given that the banks in China are owned by the government, individuals getting into money lending would be a problem. And if you are a minority, basically anyone who is not Han Chinese, forget it. There are about a million Uyghurs in internment camps right now, although the Chinese government denies it.

And what exactly is the economic system in China? Pudong, with its neon skyscrapers and the second-tallest building in the world, is Shanghai’s financial center built to rival Hong Kong, constructed in the last 20 years. China is buying up resources around the globe, building infrastructure in third world countries, so China can have access not only to minerals and resources there but also to those markets for selling Chinese goods. What could be more capitalist than that? So is this authoritarian capitalism?

not only to minerals and resources there but also to those markets for selling Chinese goods. What could be more capitalist than that? So is this authoritarian capitalism?

And what about traditional Chinese culture? I had visited China in the 1980s when people still put their birds outside in cages in the narrow lanes between housing blocks for fresh air, and old people did early morning Tai Chi in the park. Now, so many neighborhoods have been knocked down, entire blocks at a time, that many of the ones that remain are like attractions for shoppers and tourists. The French Concession, however, still has blocks of low-rise buildings and beautiful, white-bark plane trees with large leaves that look a lot like maple leaves, lining the two-lane streets and creating welcome shade from the hot August sun.

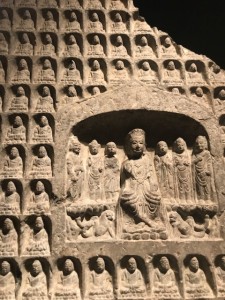

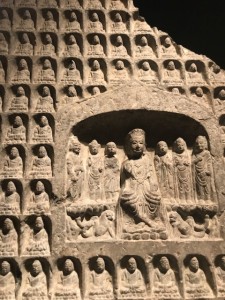

And judgi ng from the Chinese crowds at the spectacular Shanghai Museum, people very much appreciate the magnificent exhibits of ancient Chinese art. The museum is so popular that one signs says, “Here is a line of 4 hours.” Fortunately, there was no need for that sign the day I visited.

ng from the Chinese crowds at the spectacular Shanghai Museum, people very much appreciate the magnificent exhibits of ancient Chinese art. The museum is so popular that one signs says, “Here is a line of 4 hours.” Fortunately, there was no need for that sign the day I visited.

And where was the older generation? My guidebook said 25% of the people in Shanghai are over 60. I’d hardly seen any other than a few older women in what looked like comfy pajamas.

On my last morning, I got up early and left my sleek, hi-rise hotel for a walk in the tiny park nearby, an oasis of green in a traffick-y, paved-over area near the Jing An Temple. Just inside the park, a group of middle-aged Chinese women and a few men were lined up in four or five rows, doing stretching exercises to music coming from a boom box, while a woman up front led the group. It could have been an exercise class at my health club back home except for the Chinese pedestrians who rolled their luggage right through the middle of the group, crossing the park while I stood off to the side.

a few men were lined up in four or five rows, doing stretching exercises to music coming from a boom box, while a woman up front led the group. It could have been an exercise class at my health club back home except for the Chinese pedestrians who rolled their luggage right through the middle of the group, crossing the park while I stood off to the side.

I wandered around and found a group of older Chinese women wearing dresses and low blocky heels dancing in two long lines to what sounded exactly like Merle Haggard. Their dance style wasn’t sassy, the way it would be in the United States. Instead, the women looked almost bored, lifting their feet half-heartedly, stopping to chat with their friends, and raising their arms nonchalantly.

Nearby was the group I had most wanted to find. Several older Chinese men and women were practicing Tai Chi, flowing from one move to the next as if surrounded by something palpable that the rest of us could not see. One gray-haired man was particularly mesmerizing, dressed in a white shirt and loose, dark pants. I couldn’t take my eyes off him until he stepped out of the group and went to talk to some old men sitting on a wooden bench nearby.

In all, maybe eight different groups were dancing or exercising in this little park before 9 am. Skinny but healthy-looking wild cats with surprisingly un-matted fur wandered through it all, completely at home. In fact, it probably was their home.

From there, I explored another neighborhood and ended up strolling down Julu Lu, a lovely, two-lane street in the French Concession, near a creative arts center, a magazine  publisher, and a writing center. I heard classical guitar music coming from a small speaker at the Farmhouse Cafe. I stopped at the walk-up window and ordered a cappuccino. I wasn’t sure if the young Chinese man who prepared my drink would understand English, but he looked like he might be a student and I had to try. “What is that music?” I asked.

publisher, and a writing center. I heard classical guitar music coming from a small speaker at the Farmhouse Cafe. I stopped at the walk-up window and ordered a cappuccino. I wasn’t sure if the young Chinese man who prepared my drink would understand English, but he looked like he might be a student and I had to try. “What is that music?” I asked.

“Julian Bream,” he said with a smile. We grinned at each other for several moments, sharing the clear, perfect notes of Britain’s foremost classical guitarist, playing what sounded like Bach.

That formed one of my lasting impressions of this hot, crowded, ultra-modern Chinese city and was a perfect ending to my trip: an unexpected connection with a total stranger that transcended boundaries of time and culture. You never know what you will find in China. I hope you get a chance to go too.